What is a DCP (Digital Ciniema Package)?

A DCP (Digital Cinema Package) is the industry-standard delivery format cinemas use to screen films reliably and consistently, no matter which projector or cinema server is in the booth. Think of it as a structured package of files (not a single video file) that a cinema server can ingest, verify, and play back with predictable results.

A quick clarification that saves a lot of confusion:

- DCP is the package (the deliverable).

- DCI refers to the specifications that define how digital cinema should work to ensure compatibility and quality. A DCP can be made to meet DCI requirements (often what people mean by “DCI-compliant”).

If you are delivering to a cinema, a festival, or any theatrical screening where reliability matters, a properly prepared DCP is the safe default.

Why cinema requires DCP instead of video files

If you have a beautiful master in MP4, ProRes, DNxHR, or H.264/H.265, it is normal to wonder: “Why can’t the cinema just play this?”

Here’s the short, practical answer: cinema playback is a different ecosystem.

A DCP exists because cinemas need:

- Consistency across venues: different servers, different projectors, different audio chains.

- Frame-accurate playback: stable timing and sync matters on a big screen.

- High-quality image encoding designed for theatrical projection (commonly JPEG 2000 inside MXF).

- Robust packaging with metadata and integrity checks, so the cinema can ingest and verify what it received.

Video files can look great, but they are often optimized for editing or consumer playback. Cinemas need something closer to “industrial-grade delivery”: predictable, verifiable, and compatible.

The internal anatomy of a DCP folder

A DCP is a folder (or set of folders) containing media and XML metadata that tells the cinema server how to reconstruct the presentation.

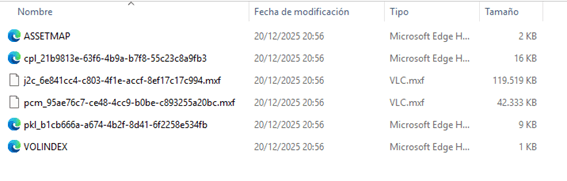

Common components you will see:

- MXF files: the containers holding picture and audio essences

- XML files: playlists and packing lists that describe what’s inside

- Asset maps / indexes: references so the server knows where everything is

Visual essence and JPEG 2000 encoding

In most theatrical DCPs, picture is encoded using JPEG 2000, typically as intraframe compression (each frame is compressed independently).

Why that matters in practice:

- Stable playback at cinema scale

- Predictable decode behavior on cinema servers

- High-quality imagery designed for big-screen projection

It also explains why DCPs are often large: the goal is not tiny files, the goal is reliable theatrical quality.

Audio track mapping and formatting

DCP audio is commonly delivered as uncompressed PCM inside an MXF container, with standardized channel layouts such as:

- 5.1 (L, R, C, LFE, Ls, Rs)

- 7.1 (adds additional surround channels, depending on format)

What matters most is not only “5.1 vs 7.1”, but correct channel mapping. A wrong mapping can turn dialogue into surrounds, put music in the center channel, or cause weird level issues that no one wants to discover at the premiere.

Critical Audio Channel Mapping (5.1 Standard)

Most theatrical screening issues occur because the audio channels were exported in the wrong order (e.g., SMPTE vs. Film order). For a DCP, the tracks must be mapped as follows:

- Track 1: Left (L)

- Track 2: Right (R)

- Track 3: Center (C) ⚠️ (Dialogue must be placed here)

- Track 4: LFE (Subwoofer)

- Track 5: Left Surround (Ls)

- Track 6: Right Surround (Rs)

⚠️ Tech Note for Post-Production: If you are sending these specs to your editor, please include the following instruction: “Please ensure all master files are delivered with the discrete 5.1 mapping listed above to avoid phase or dialogue displacement during the DCP encoding process.”

Data files and metadata

The XML files are the instructions that make the DCP behave like a “cinema-ready show” instead of a random set of media files.

You will often see:

- CPL (Composition Playlist): how the presentation is assembled (which picture/audio assets, in what order)

- PKL (Packing List): what assets are included, plus integrity information

- AssetMap / VOLINDEX: the directory map the server uses to locate assets

In plain terms: the MXFs contain the media, and the XML files tell the server how to play it correctly.

Technical standards and specifications

DCPs are designed to be compatible with cinema servers worldwide, but there are still important technical choices that affect whether your DCP plays everywhere without drama.

Key areas:

- Interop vs SMPTE

- 2K vs 4K

- Flat vs Scope containers

- Frame rates

- Color space requirements

Understanding Interop vs SMPTE formats

This is one of the most common “hidden” decisions in DCP delivery.

- Interop: older, widely supported, often chosen for maximum legacy compatibility.

- SMPTE: newer, more modern standard, supports more features and use cases.

A practical rule many teams follow:

- If you need maximum compatibility, especially with older systems, Interop can be safer.

- If you need modern features or wider format support, SMPTE is often the right choice.

For festivals, mixed venue setups are common. That is why compatibility planning matters as much as the encode.

Resolution and aspect ratio guidelines

In DCP land, you often work with standardized “containers.” The two most common are:

- Flat (roughly 1.85:1)

- Scope (roughly 2.39:1)

Your actual content might be native Flat/Scope, or it may be letterboxed/pillarboxed inside a container. The goal is predictable projection and correct masking.

A simple way to think about it:

- Choose the correct container for the intended presentation.

- Ensure framing is correct and intentional.

- Avoid surprises like unintended cropping or extra black bars.

DCI Standard Resolution Reference Table

Standard DCI Resolutions Reference:

| Format | Container Resolution | Aspect Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 2K Flat | 1998 x 1080 | 1.85:1 |

| 2K Scope | 2048 x 858 | 2.39:1 |

| 4K Flat | 3996 x 2160 | 1.85:1 |

| 4K Scope | 4096 x 1716 | 2.39:1 |

Note: Unlike consumer UHD (3840×2160), DCI 4K uses full industrial resolutions.

Frame rates

DCPs can be made at different frame rates. In practice, 24 and 25 are very common, depending on production and delivery territory.

What matters is not only “can a DCP be made at X”, but:

- Is the target venue compatible with that rate?

- Does the format choice (Interop vs SMPTE) affect support?

- Has it been tested on real cinema equipment?

If your DCP is for a festival with multiple cinemas, it is smart to confirm the required delivery specs early.

Color space and gamma requirements

Most masters are in Rec.709 (common for online and broadcast). Cinemas typically expect DCP picture in DCI X’Y’Z’ with a different gamma behavior.

This is one of the easiest places to lose quality if the workflow is not handled properly. A correct conversion ensures:

- predictable color reproduction on cinema projectors

- fewer surprises with contrast and perceived brightness

- a more consistent look across venues

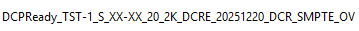

Decoding the digital cinema naming convention

If you have ever seen a DCP name that looks like a long technical code, that is not an accident. The ISDCF naming convention helps projectionists and festivals identify key details at a glance.

Typical naming communicates things like:

- title and version

- container ratio (Flat/Scope)

- resolution (2K/4K)

- audio type (2.0/5.1/7.1)

- language and subtitles

- whether it is an original version (OV) or a version file (VF)

Essential fields in the naming string

Even if you never build names manually, you should be able to read the important parts:

- Content title: what it is

- Versioning: which cut or deliverable

- Picture format: ratio, resolution

- Audio format: channel configuration

- Language and subtitle info: especially important for festivals

A clear, correct name prevents mistakes at scheduling time.

Common naming mistakes to avoid

These are the classic issues we see in real deliveries:

- Wrong language or subtitle codes (causes confusion for festivals or cinemas)

- Incorrect OV/VF usage (can break workflows that expect both)

- Mismatched Flat/Scope labels versus actual framing

- Reusing names across different versions (hard to track, easy to screen the wrong file)

Good naming is not cosmetic. It is operational safety.

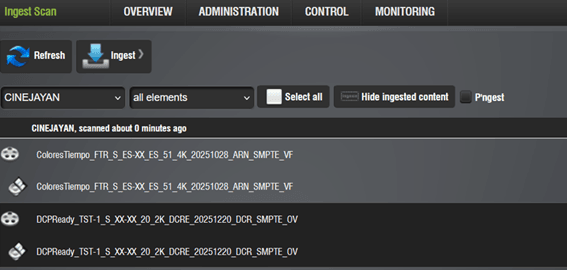

How a cinema actually plays a DCP

This is the part most people never see, but it explains why DCPs are built the way they are.

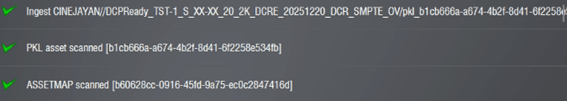

A typical cinema workflow looks like this:

- Ingest: The cinema copies the DCP from a drive or over a network onto the cinema server.

- Verify: The server checks the package integrity and makes sure it can read the assets.

- Program: The projectionist builds a playlist (trailers, ads, feature, subtitles if applicable).

- Play: The server decodes the content and sends picture and sound through the cinema chain.

In real life, many delivery problems happen before anyone presses “Play”:

- drive format issues

- incomplete copies

- wrong metadata or naming

- subtitle mismatches

- encryption and key issues

That is why DCP is not only about quality. It is also about operational reliability.

Encryption and key delivery messages (KDMs)

Encryption in digital cinema protects content from unauthorized playback. The content is locked, and a cinema needs a KDM (Key Delivery Message) to unlock it for a specific server, content and within a specific time window.

When to use encryption (and when not to)

Encryption is useful when:

- you need strict control over where and when content can play

- rights holders require it

- the release is sensitive (premieres, pre-release screenings)

Encryption can be painful when:

- you have many venues (festivals)

- schedules change at the last minute

- servers get swapped

- someone forgets that keys have validity windows

For many festivals, the added logistics can outweigh the benefit unless encryption is required.

Operational pitfalls (time windows and delivery)

Most KDM issues are not “technical crypto problems.” They are operational:

- The KDM is valid for the wrong dates

- The KDM was generated for the wrong server certificate

- The screening moved, the KDM did not

- A replacement server or media block appears, and the KDM no longer matches

If you are encrypting, treat KDM management as part of the deliverable, not an afterthought.

Best practices for physical and digital delivery

A DCP can be perfect and still fail in the real world if delivery is sloppy.

Physical delivery (drives)

Common best practices:

- Use reliable drives and docks commonly used in cinema workflows (CRU-style docks are common in some environments).

- Format drives in a filesystem that the target venue supports (many venues expect Linux-friendly formats).

- Avoid “mystery partitions” and consumer backup tools that change file attributes.

Digital delivery (transfer)

If transferring electronically:

- Use tools that handle large files safely.

- Avoid zipping unless the receiving workflow explicitly requests it.

- Always verify that what arrived is complete and uncorrupted.

The most common delivery mistakes (Top 5)

- Incomplete copy or interrupted transfer

- Wrong drive formatting for the cinema server

- Unzipping or repackaging that changes structure

- Missing or mismatched subtitles / metadata

- KDM issues (wrong server, wrong window)

This is where a professional DCP workflow saves time and stress.

Professional DCP creation services

If you want your film to screen exactly as intended, a DCP should be treated as a real mastering deliverable, not a last-minute export.

With DCPReady, the goal is simple: a cinema-ready, DCI-aligned DCP that plays reliably, plus the checks that prevent surprises.

What you typically get:

- A properly packaged DCP (Interop or SMPTE as required)

- Correct picture and audio mapping

- Delivery-ready folder structure and naming

- Practical QC focused on real-world cinema playback

If you want a quick, clear path from master file to theatrical delivery.